This blog post is Human-Centered Content: Written by humans for humans.

Traffic control agencies rely on vast CCTV networks to keep roads safe. But when something goes wrong, figuring out what happened is still a slow, manual process.

Imagine this: A spill of sand is reported on a busy highway, and the agency now has to hunt through hours of archived footage to find the vehicle responsible. Traditionally, operators would spend countless hours watching, rewinding and cross‑checking feeds to piece it together.

But what if they could simply type a natural‑language query and instantly retrieve the most relevant video segments?

In this article, I’ll show how that’s possible, using Snowflake and Twelve Labs to build a semantic video search solution. To keep things concrete, I’ll use real CCTV footage (video here) from a busy highway, focusing on the segment between 0:40 and 2:30.

Let’s get to work.

Core Technologies

Before delving into the solution itself, it’s important to briefly mention several key technologies the solution is built upon:

- Vectors are mathematical representations of objects, expressed as ordered lists of numbers where each number is one dimension or feature. When we use vectors with many such dimensions (often hundreds or thousands) to represent things like text, images, videos or audio, we call them embeddings.

- Snowflake can store vectors natively, which means that those embeddings can be queried and joined just like any other column.

- Twelve Labs. A video understanding platform that encodes objects into embeddings. In the case of videos, it splits them into segments and turns each segment into a vector.

- To compare different vectors, Snowflake also provides the function VECTOR_COSINE_SIMILARITY. What does this do? In essence it tells us how “similar” two vectors are. Mathematically there’s much more going on under the hood. This IBM article is a great introductory read.

These definitions are, of course, very introductory. Any production implementation will demand a deeper understanding but hopefully this blog gives you a headstart.

Solution Overview in Snowflake

Now let’s focus on the solution itself. In essence, this implementation allows users to find in a video what they just describe in plain language.

To do so the system uses Twelve Labs to turn both the video and the text query into numerical embeddings, it then compares these vectors with cosine similarity and scores each video segment based on its relevance to the text query from the user.

For the best‑matching segments, the system also generates still frames and has an LLM score how well each image matches the user’s initial text query. This returns an LLM score that is combined with the similarity scores mentioned earlier to produce a final ranking so the most relevant frames, that is, those identified by Twelve Labs and reviewed and validated by an LLM, are surfaced back to the user.

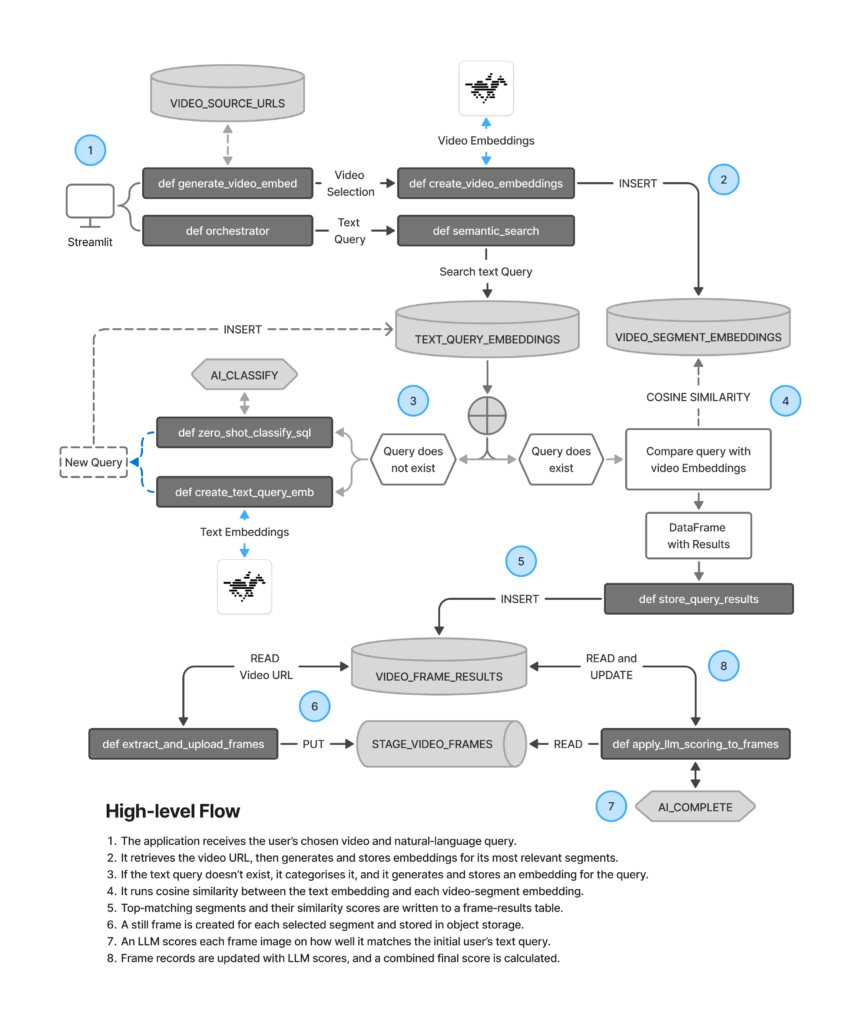

All these steps can be executed directly in Snowflake — for example in a Notebook or another orchestration layer — through a series of functions that I have outlined in the diagram below:

The next section covers the key building blocks of the overall solution, which was inspired by this tutorial here from Twelve Labs. I will keep the explanation conceptual: I am including pseudo-code of each key component, understanding that you can find the full code available in this GitHub repository. Let’s get into it.

Encoding Objects into Vectors

First, we need three functions, one to encode each type of data: images, videos and text. To make the solution more manageable and scalable you will see I rely heavily on parameters for source and target objects.

Let’s start with images. Simply put, this function receives one or more image URLs, turns each of them into a vector embedding (those numerical representations mentioned earlier) and persists them into a table. That’s it.

# Pseudo code

def create_and_store_reference_image_embedding(url) -> list:

# Call Twelve Labs to get an embedding for the image

response = twelvelabs_client.embed.create(

model_name=CHOSEN_MODEL,

image_url=url

)

# Pull the vector for the first returned segment

embedding_vector = response.embeddings

# INSERT data as VECTOR into a table

insert_sql = f"""

INSERT INTO {REFERENCE_IMAGE_EMBEDDINGS_FQN}

()

SELECT

...

ARRAY_CONSTRUCT({embedding_vector})::VECTOR(FLOAT, 1024)

"""

# Persist the embedding in Snowflake

session.sql(insert_sql).collect()

return embedding_vector

Next comes a function to encode text. This will be used to get a vector embedding of the natural‑language question posed by the user. Again, we encode it, persist it and return a query ID.

# Pseudo code

def create_and_store_text_query_embedding(text_query: str) -> int:

"""Create a text embedding for a query, store it and return its id."""

# Call Twelve Labs to embed the natural-language query

response = twelvelabs_client.embed.create(

model_name=CHOSEN_MODEL,

text=text_query,

text_truncate="start"

)

# Extract the vector for the first text segment

embedding_vector = response.text_embedding

# INSERT data as VECTOR into a table

insert_sql = f"""

INSERT INTO

...

ARRAY_CONSTRUCT({embedding_vector})::VECTOR(FLOAT, 1024)

"""

session.sql(insert_sql).collect()

# Fetch the latest QUERY_ID for this query

insert_async_job = session.sql(insert_sql).collect(block=False)

...

# Retrieve query ID for

async job insert_query_id = insert_async_job.query_id

"""

result_df = session.sql(select_sql).to_pandas()

return int(result_df["QUERY_ID"].iloc[0])

Lastly, there is a function to create embeddings from a video. This one has three main differences compared to the other two:

- The Twelve Labs API responds with multiple rows: it takes the full video, splits it into segments and returns the vector plus start and end times for each segment.

- Because of that, I am creating it as a UDTF and therefore it returns a table.

- This UDTF is persisted: This allows me to get Snowflake to handle concurrency and resource management and avoid the notebook kernel to potentially become a bottleneck. This is unlikely in this case, but just best practice for computationally-expensive operations.

The results of this function are also persisted, but that is done with Python because Python UDTFs cannot execute SQL against Snowflake objects (as they don’t receive a Snowpark Session). My colleague Chris wrote a great article on this if you’re interested on the subject.

# Pseudo Code

@udtf(

name="create_video_embeddings",

packages=["..."],

external_access_integrations=["..."],

secrets={"cred": "..."},

if_not_exists=True,

is_permanent=True,

stage_location=f"@{UDFS_STAGE_FQN}",

output_schema=StructType([

...

])

)

class CreateVideoEmbeddings:

def __init__(self):

# Initialise Twelve Labs client using secret from Snowflake

twelve_labs_api_key = _snowflake.get_generic_secret_string("cred")

self.twelvelabs_client = TwelveLabs(api_key=twelve_labs_api_key)

def process(self, video_url: str) -> Iterable[Tuple[list, float, float, str]]:

# Submit an embedding task for the video URL

task = self.twelvelabs_client.embed.task.create(

model_name=CHOSEN_MODEL,

video_url=video_url

)

# Yield one row per video segment with its embedding and offsets

for segment in task.video_embedding.segments:

yield (

...

)

Establishing Comparisons Between Embeddings

So far, we have three working functions that generate embeddings for each type of data (text, images and videos) using the Twelve Labs API. Let’s now get the cosine similarity between the user’s text query and the segments short-listed.

The below function should be fairly intuitive: It iterates over a list of questions and, for each of them, it firsts check if they’ve been asked before. If they haven’t, it creates them using helper functions (you can see them in the Github repository). Then it runs VECTOR_COSINE_SIMILARITY to generate a score that is stored. Note that the function also returns an LLM_SCORE that it’s hardcoded as 0.0. This is a placeholder value. More on this in the next section.

# Pseudo code

def semantic_search(questions: list[str]) -> dict:

"""

Create query embedding if it doesn't exist,

execute semantic search over video segments,

and return results.

"""

for q in questions:

# Check if an existing embedding for the query already exists in the database

existing_sql = f"""

SELECT ...

"""

existing_df = session.sql(existing_sql).to_pandas()

if not existing_df.empty:

# Use the most recent embedding and classification if found

query_id = ... # query id from existing_df

category_zero_shot = ... # category from existing_df

else:

# Create new query embedding if one doesn't exist

query_id = create_and_store_text_query_embedding(q)

# Perform zero-shot classification on the query text

category_zero_shot = zero_shot_classify_sql(

q,

ZERO_SHOT_CATEGORIES

)

if category_zero_shot is not None:

# Update embedding table to include the zero-shot category

update_sql = f"""

UPDATE ...

"""

session.sql(update_sql).collect()

# Build semantic similarity between query embedding and video segments

sql = f"""

WITH selected_query AS (

SELECT ...

),

base_sim AS (

SELECT

...,

ROUND(

VECTOR_COSINE_SIMILARITY(

v.EMBEDDING::VECTOR(FLOAT, 1024),

q.QUERY_EMBEDDING::VECTOR(FLOAT, 1024)

),

4

) AS SIMILARITY_SCORE

FROM {VIDEO_SEGMENT_EMBEDDINGS_TABLE_FQN} v

CROSS JOIN selected_query q

)

SELECT

...,

0.0 AS LLM_SCORE,

SIMILARITY_SCORE AS FINAL_SCORE

FROM base_sim

ORDER BY FINAL_SCORE DESC

"""

# Execute SQL search and fetch results into a dataframe

full_df = session.sql(sql).to_pandas()

# Return structured search results for the query

return {

...

}

Generating Frames and LLM Scores

Now we have a ranked list of video segments that look highly relevant to the user’s query thanks to the Twelve Labs technology. But let’s take it one step further. What if we could also look at a frame from each of those video segments and have an LLM double‑check the user’s query against the actual image?

What we do here is effectively embedding retrieval with multimodal re‑ranking which, in essence it allows us to complement the accuracy of Twelve Labs with that of an LLM. Let’s see how we can do this.

Extracting and Storing Frames

A first function downloads the same video analyzed earlier and captures and stores a still image of the middle of each selected segment. We also generate the path of that file:

# Pseudo code

def extract_and_upload_frames(video_url: str, ...) -> dict:

# Check if frames already exist for this QUERY_ID

existing_sql = f"""

SELECT COUNT(*) ...

"""

existing_df = session.sql(existing_sql).to_pandas()

# If CNT > 0, skip extraction and return

# ...

# Download the video once to a temp file

response = requests.get(video_url, ...)

tmp_path = "temp_video_path"

# Open the video and iterate over segments

clip = VideoFileClip(tmp_path)

frame_map = {}

for _, row in segments_df.iterrows():

start_offset = ...

end_offset = ...

result_id = ...

# Compute a representative timestamp

frame_timestamp = start_offset + (end_offset - start_offset) / 2.0

# Capture frame at that timestamp

frame_array = clip.get_frame(frame_timestamp)

img_tmp_path = "temp_image_path"

# Upload frame to stage

put_result = session.file.put(...)

relative_path = put_result[0].target

# Update FRAME_STAGE_PATH in the results table

update_sql = f"""

UPDATE {query_result_frames_fqn}

SET FRAME_STAGE_PATH = '{relative_path}'

WHERE ...

"""

session.sql(update_sql).collect()

frame_map[result_id] = relative_path

# Return a simple mapping of segment to frame path

return frame_map

Applying LLM Scoring to Frames

Second, another function takes the stored frames we generated earlier and calls an LLM to score how well each image matches the user’s question. A final similarity score (considering Twelve Labs and the LLM) is generated. It’s important to note that with this setup, we’re effectively giving equal weight to both scores. In more advanced flows, we could introduce explicit weights or exponents that could be adjusted based on evaluations or user feedback, but we will keep it simple here:

# Pseudo code

def apply_llm_scoring_to_frames(

query_id,

...

) -> None:

# Build a stage string with DB and schema

stage_string = f"..."

# Create a temp table with LLM scores for each frame

sql_scored = f"""

CREATE OR REPLACE TEMP TABLE LLM_FRAME_SCORES AS

SELECT

...,

SNOWFLAKE.CORTEX.COMPLETE(

'claude-4-sonnet',

PROMPT(

'You are a traffic analysis assistant ... {user_query} ...',

TO_FILE('{stage_string}', v.FRAME_STAGE_PATH)

)

)::FLOAT AS LLM_RAW

FROM {video_frame_results_fqn} v

WHERE

...

"""

session.sql(sql_scored).collect()

# Update main table with LLM_SCORE and FINAL_SCORE

sql_update = f"""

UPDATE {video_frame_results_fqn} t

SET

LLM_SCORE = s.LLM_RAW,

FINAL_SCORE = t.SIMILARITY_SCORE * s.LLM_RAW

FROM LLM_FRAME_SCORES s

WHERE

...

"""

session.sql(sql_update).collect()

Orchestrating the Search Flow

Now that we have the building blocks ready, we need a thin orchestration layer to glue everything together. I created a function called def orchestrate_video_search_and_frames that, at a high level, takes a user question and a video URL and coordinates the execution of all the functions we spoke about earlier. I won’t cover it here as is quite simple but what matters is its final output: a ranked set of frames ready to display.

This covers the bulk of the setup needed. Again, you can see the full code used in this GitHub repository, including a basic Streamlit app that will act as the front end. We are now ready to start processing natural‑language queries against the video.

Walking Through the Sand‑Truck Example

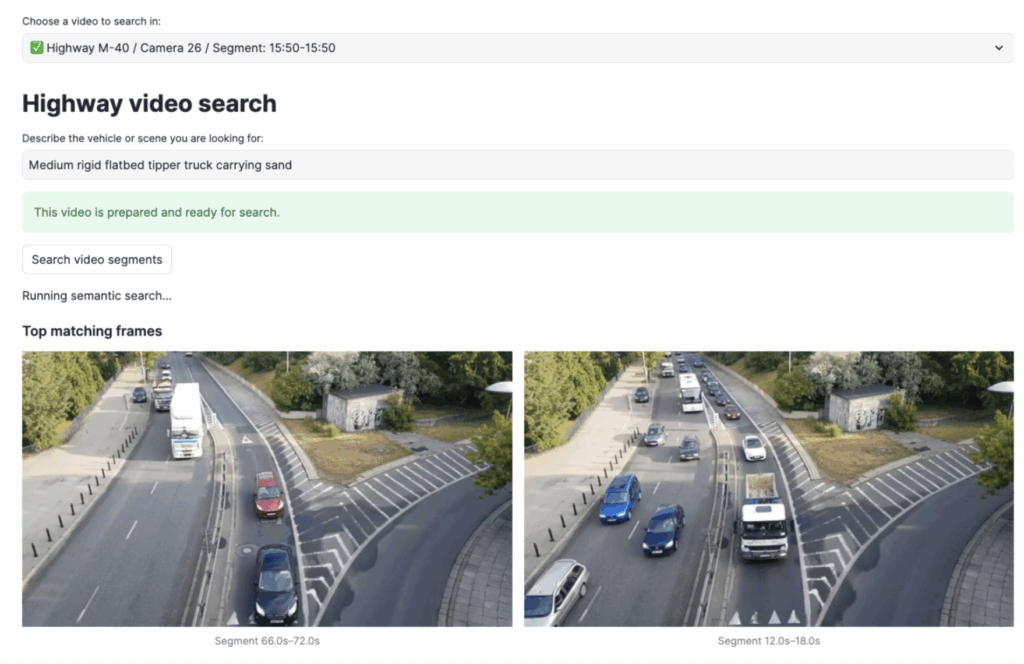

To bring all of this to life and circle back to the use case at hand, we will pass the following query to our solution:

[user question]

“Medium rigid flatbed tipper truck carrying sand.”

And lift off! The application display six relevant video segments:

Impressive. But wait, what happened here?

A Peak Behind the Scenes

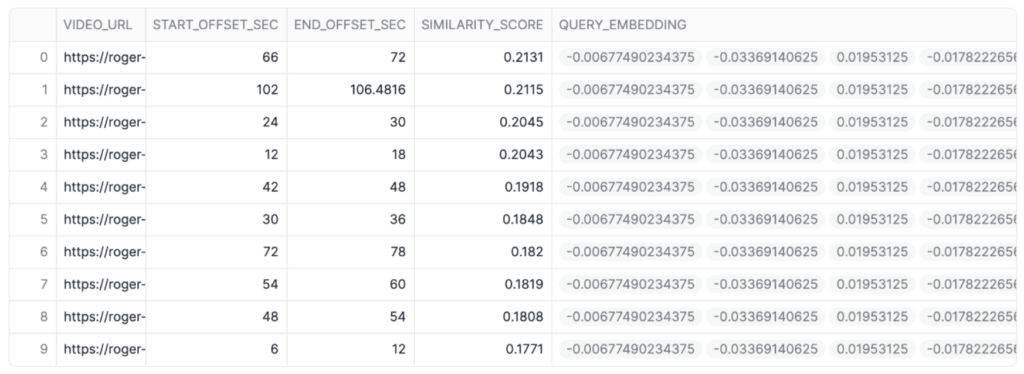

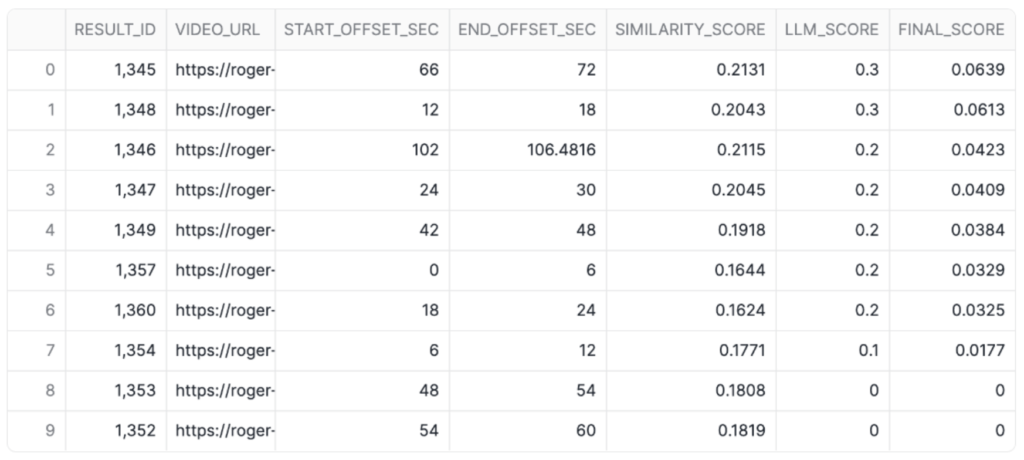

The moment we trigger our pipeline, Twelve Labs splits the entire video into several segments. For each of them, it returns the start time, end time and corresponding embeddings. In the screenshot below, you can see that raw output plus the similarity score, which is the result of the cosine algorithm between the segment and the text query.

Above: Embeddings of each video segment scored against our text query.

Above: Embeddings of each video segment scored against our text query.

Then, the pipeline takes a screenshot of the midpoint of each video segment and sends that image to an LLM that evaluates the question against it and returns a score. A final score is produced, which the Streamlit App displays in the front end.

Above: Similarity, LLM, and final score for each video segment against our text query.

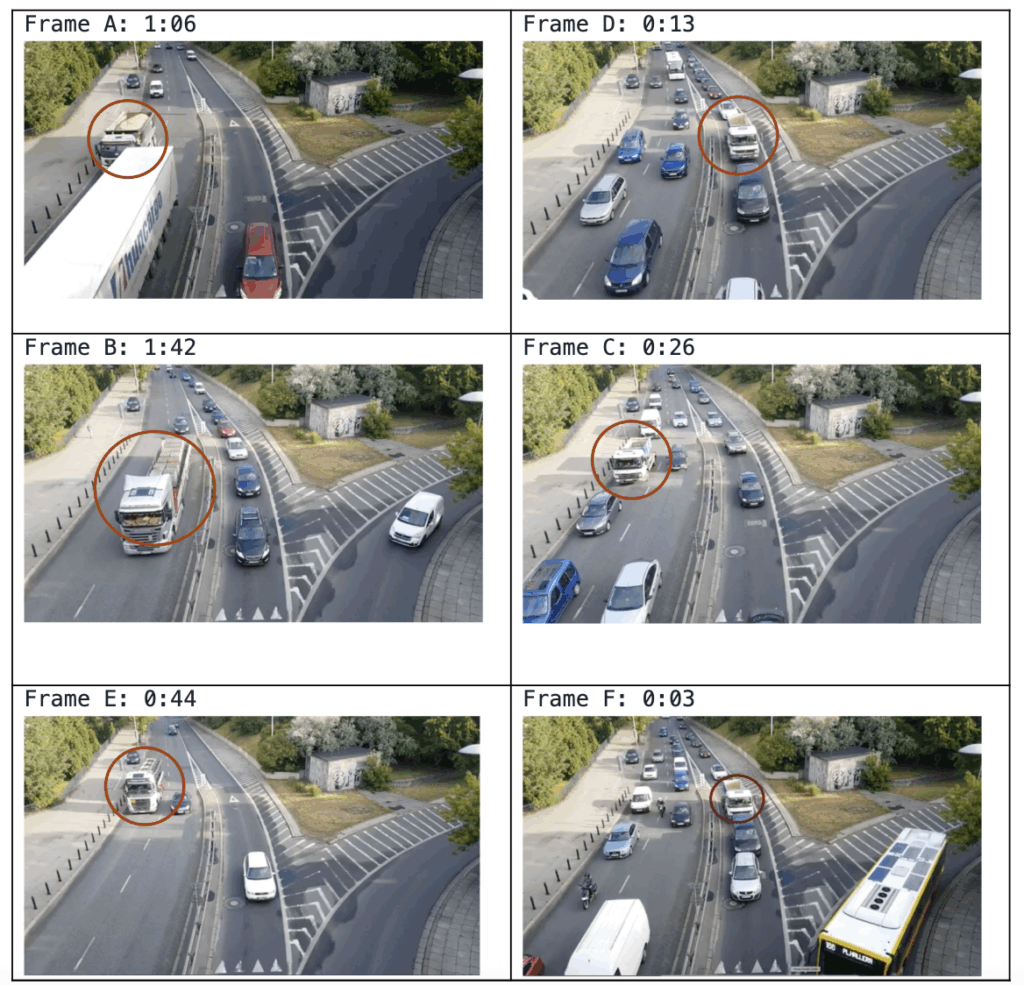

The above table perhaps does not mean much in the abstract, so using the offsets provided I have mapped the top six results to frames in the video to illustrate what the pipeline actually saw in the raw footage:

Above: Frames of the video with highest scores compared to our text query.

What do we observe above?

- Frame A indeed depicts a truck carrying a visible load of sand. Impressive. Remember, the question used was “Medium rigid flatbed tipper truck carrying sand.”

- Frames C, D and F are flatbed or tipper trucks that align structurally with the query but appear empty. Having watched the entire clip, this is still pretty good: There are several other trucks in the footage that were correctly not flagged.

- Frames B and E are trucks, but do not carry any sand. This would be a good opportunity to implement a more robust RAG layer to increase even more the efficiency of our pipeline.

Closing Thoughts

This prototype focuses on a single camera and a single motorway segment, yet the same pattern can extend to dozens of feeds and a wide range of scenarios. By persisting embeddings and metadata in Snowflake, organisations can join video search results with existing operational datasets to build richer insights.

Treating video as a searchable, vectorised dataset allows teams to ask complex, natural‑language questions of their footage and receive targeted, explainable hits instead of relying on manual scrubbing. By combining Twelve Labs’ video understanding with Snowflake’s vector functions and a small library of positive and negative reference images, the solution shows how even nuanced scenarios become tractable at scale.

Do you need help with your implementation? Do feel free to reach out.