What does this mean anyways, “Tableau Governance”? Search the web and this phrase will turn up countless articles that instruct on running your Tableau Server yet often feel fleeting because they describe an environment that’s not your own. Perhaps your organization’s use of Tableau feels more complex than the idyllic scenarios described in many knowledge bases, and while “Best Practices” sound great in theory, they are hard to translate to your use case.

This series on Tableau governance will draw key learnings from three varied governance solutions that we’ve built to suit our clients. After all, InterWorks knows that a governance solution should be as unique as the organization it serves. You’ll notice that we make frequent mention of “Core Principles” introduced in our Tableau Governance 101 Webinar, which is certainly worth a watch as you ponder a place for governance in your organization.

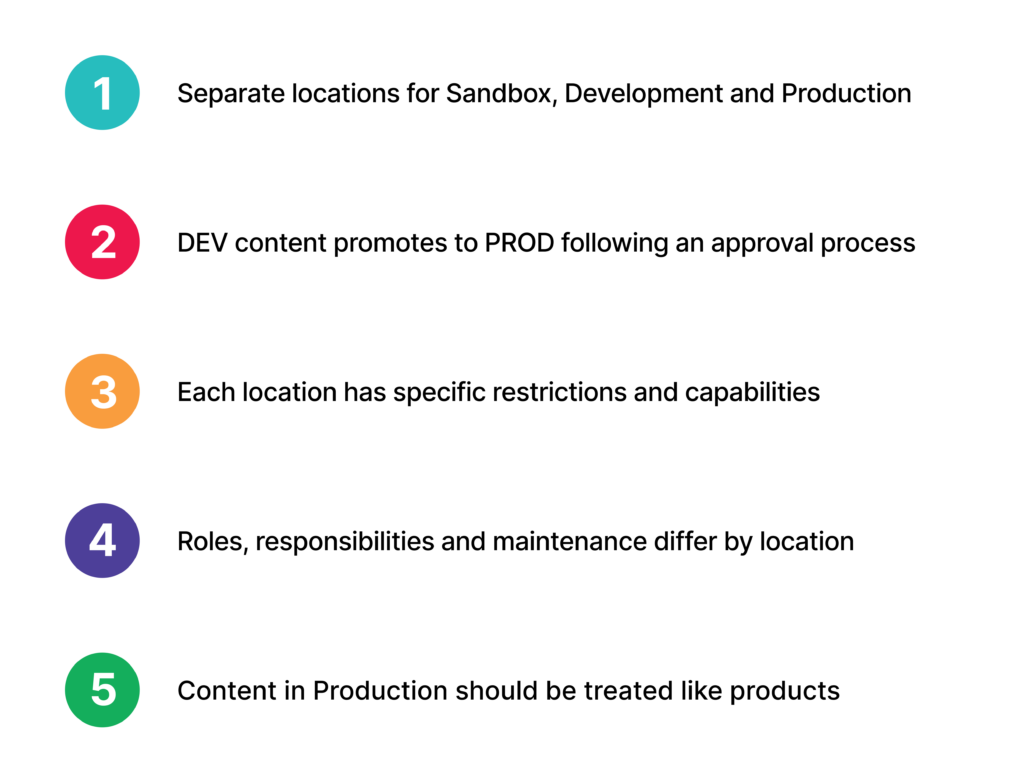

If you’ve not yet viewed that webinar, these core principles are as follows:

Without further delay, let’s examine our first solution!

Situation: Organization desired greater transparency of Tableau Server content

Context: Medical devices company with approximately 20 Creators and 100 Viewers

Our Recommendation: (Structured) Flexibility

Guiding Principles:

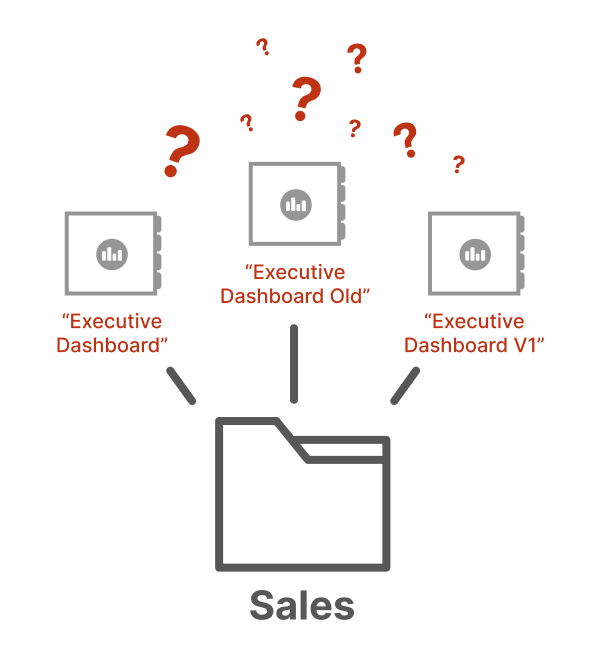

At times, a need for strategic permissions in Tableau feels obvious, especially in the case where certain parties should (or should not) see published content prior to its productionalization on the server. Consider the implications of a sales manager logging into Tableau and accidentally opening a version of their Executive Report, which (unbeknownst to them) is in development, and the connected data source hasn’t updated for days. Inconvenience, confusion and frustration are all things they’d surely experience as they try to make sense of that dashboard.

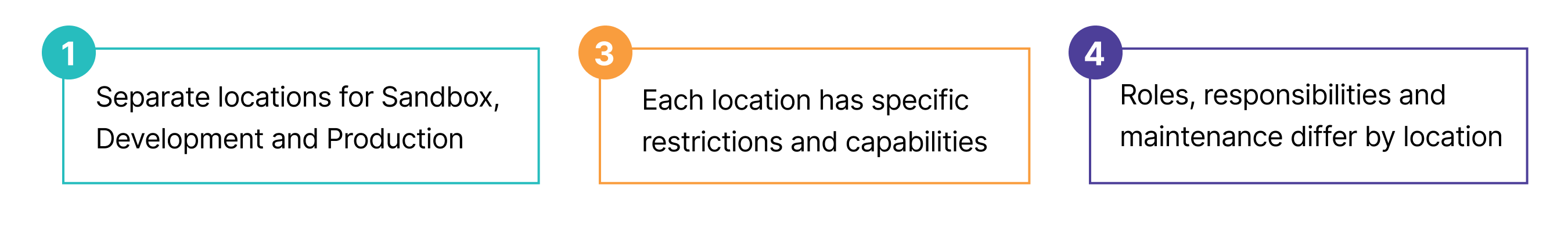

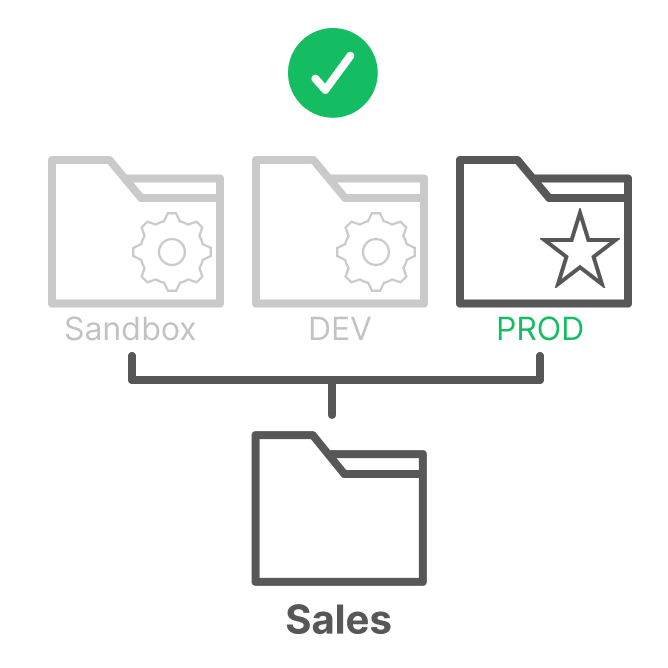

This scenario is the foundation for Tableau governance Principles 1 and 3, which suggest that separate locations with differing restrictions and capabilities exist for published content in varying stages of development (for example, Sandbox/DEV/PROD). These principles solve for the scenario mentioned above, in that the sales manager would only receive permissions to access reports in the production location, barring any risk of them accidentally opening a test version that, in the absence of this suggested project structure, could otherwise be sitting among the production version of the same report.

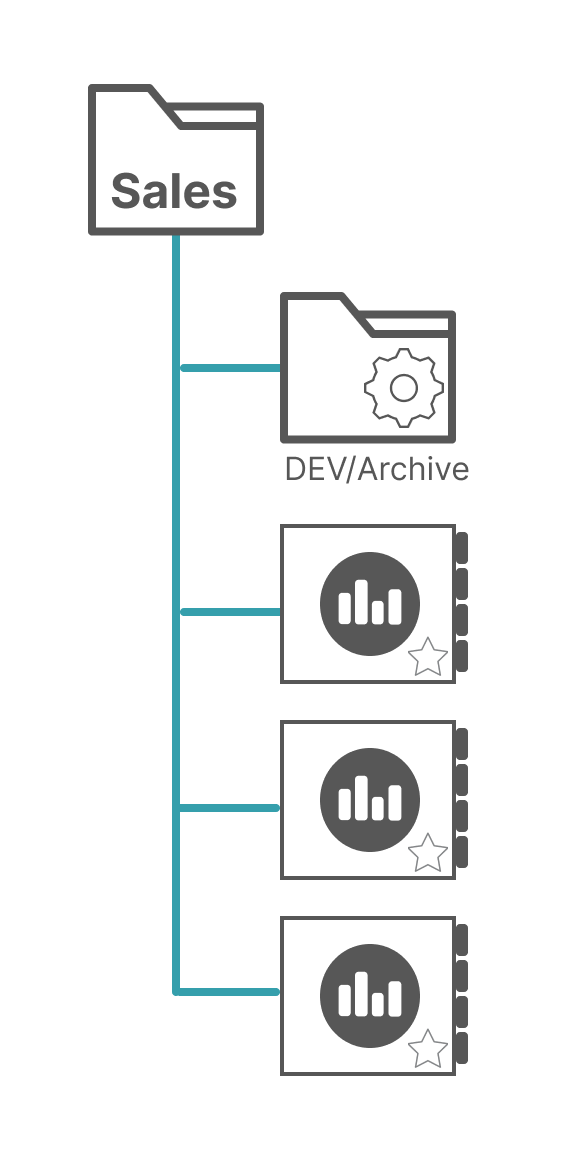

However, for some organizations, this degree of governance through permissions feels unnecessary, as was the case with a client who preferred that broader visibility of content in development be permitted to all parties. In response, we proposed a variation of Principle 3 (each location has specific restrictions and capabilities) in which project descriptions were used in lieu of permissions to create transparency around the status of content in each location. Furthermore, we simplified the proposed project structure in Principle 1 and established a top-level project into which production content would be directly published. Within the top-level project, a sub-project was created to house content in development or archived/out of date. This sub-project essentially became a catch-all for non-production content and was labeled as such.

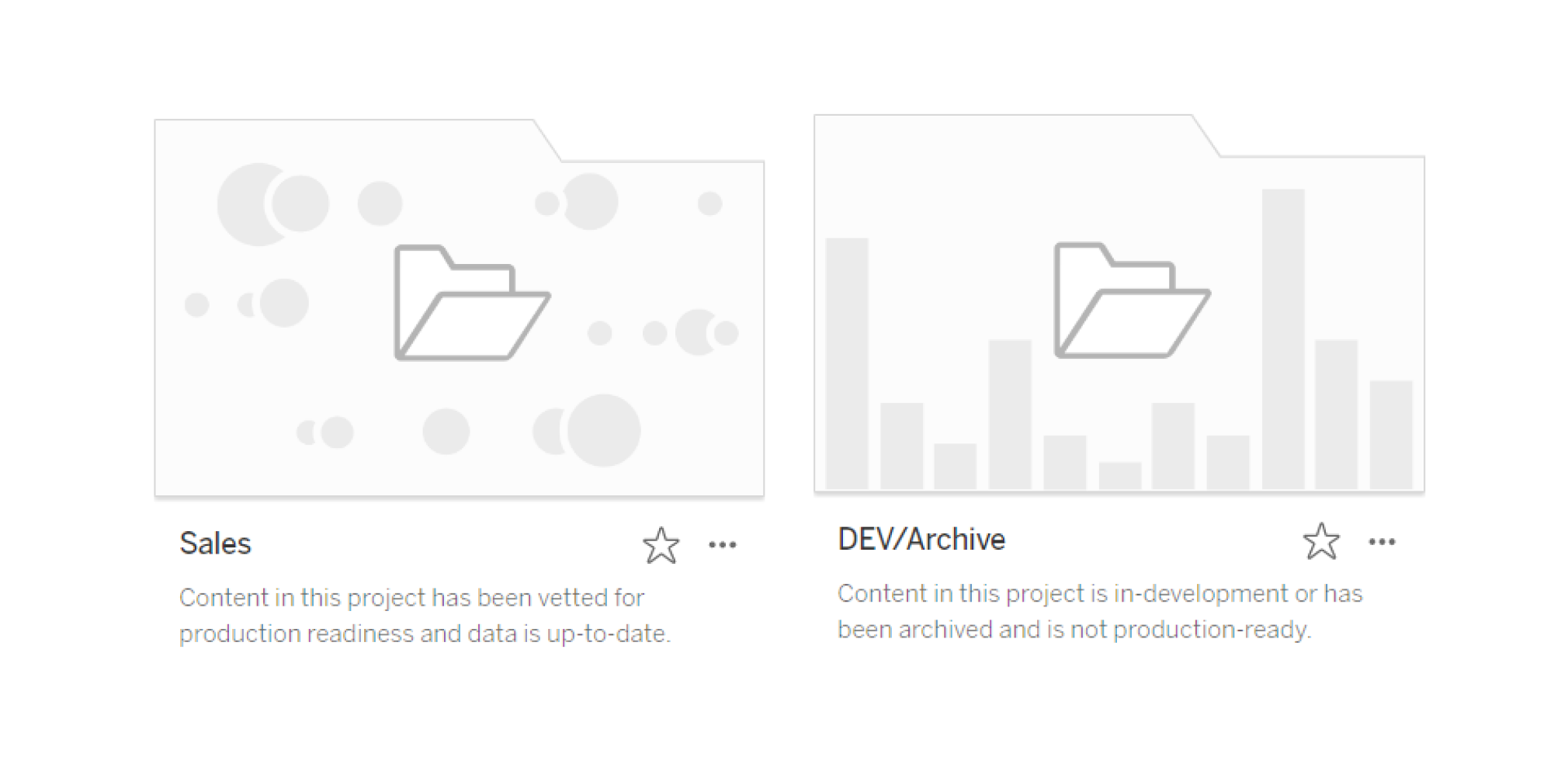

Permissions on the top-level Sales project remained the same as those in the DEV/Archive project which nested underneath it, however, descriptions were added to all projects to make the status of content inside very clear. This meant that although stakeholders had visibility to the DEV/Archive project, there was no ambiguity about the content it held as being not fit for production.

Here’s an example of how these descriptions were applied to the model detailed above.

In further alignment with Principle 3, we recommended that extracts in the DEV/archive projects not be scheduled for refresh. Instead, at the time a workbook is published to production, developers would also publish any supporting data sources into production and schedule extract refreshes as necessary. As such, the resource-intensive activity of refreshing extracts is reserved for production content, which is used for decision making.

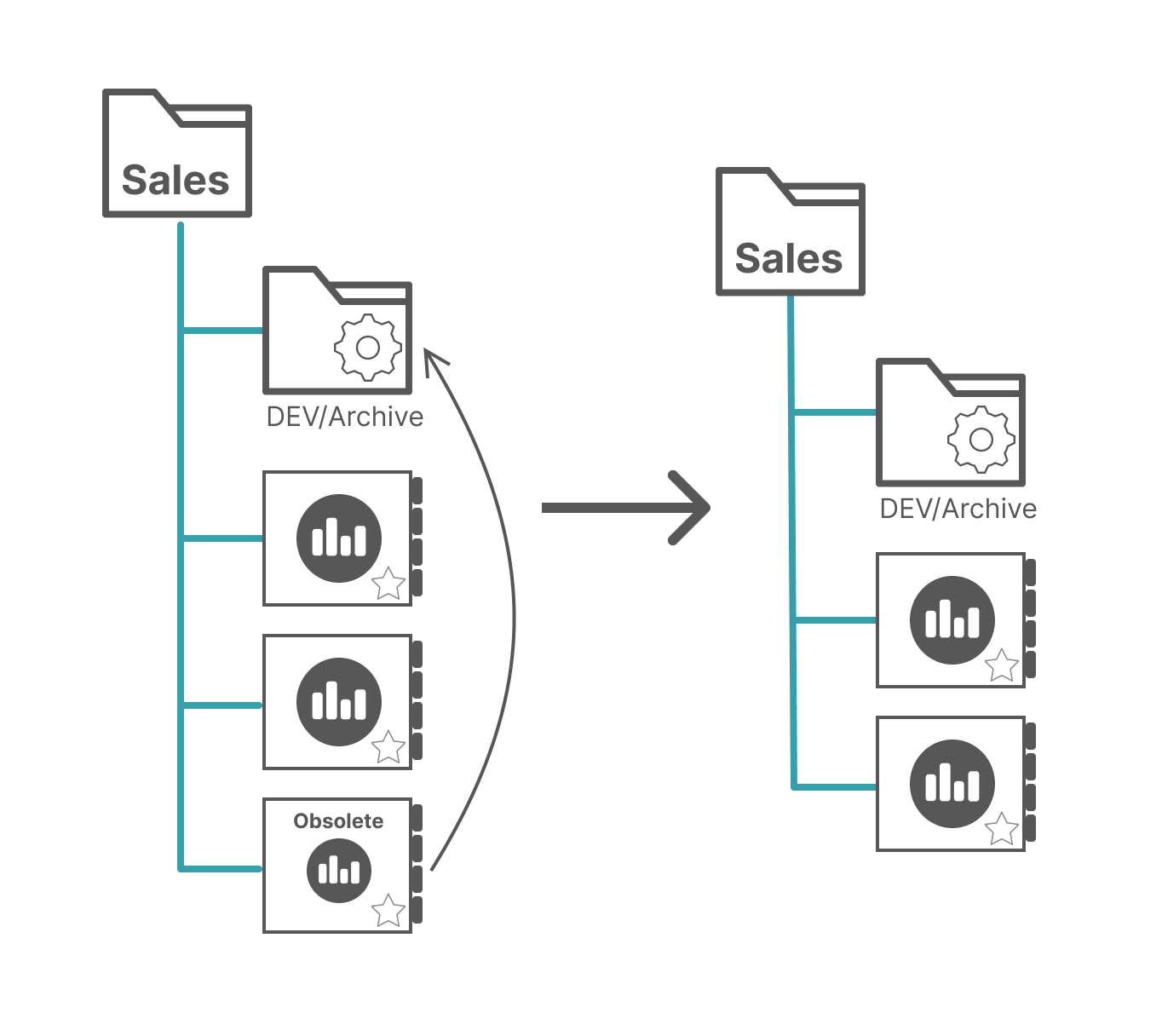

To the extent that this client wished to have all content visible to their users, we devised a plan for stale content review per Principle 4, which would happen on a more approachable quarterly basis. Especially in the case of exposing DEV/Archive spaces to all users, periodic archival and eventual removal of old content will keep your users on track in pursuit of their dashboards and minimize clutter on your site.

This client exhibited how the governance principles can be applied flexibly to accommodate fewer restrictions around content viewing, while still preserving the integrity of the production space. Through a modified project structure and well-maintained descriptions, users were clear about the status of content in each folder on the server.

In the next blog of this series on custom Tableau governance solutions, we’ll see how our principles were employed to support a client’s more rigid governance model. Have questions or want to discuss Tableau governance in further detail with our passionate team at InterWorks? Governance 360 by InterWorks offers an evaluation of your Tableau site with recommendations tailored to your governance needs. Let’s have a chat today!